BACK TO "ARCADIA"

Seeing Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia in London at the National Theater in the Spring of 1993 may have changed me forever. Or not at all. The essence of the play’s exploration of certainty and uncertainty, order and disorder, delighted and dazzled me, but made no immediate difference in my overall existence. I don’t think. The loss of one of the play’s central characters, however, late in the second act, 16-year-old Thomasina Coverly, left me so bereft that I still tear up typing these words. I cannot entirely explain why.

That is the mysterious power of Arcadia. It evokes more than the sum of its marvelously overelaborated, intricately deconstructed parts. It is a work of theatrical magic, which is to say, a play. A miraculous play.

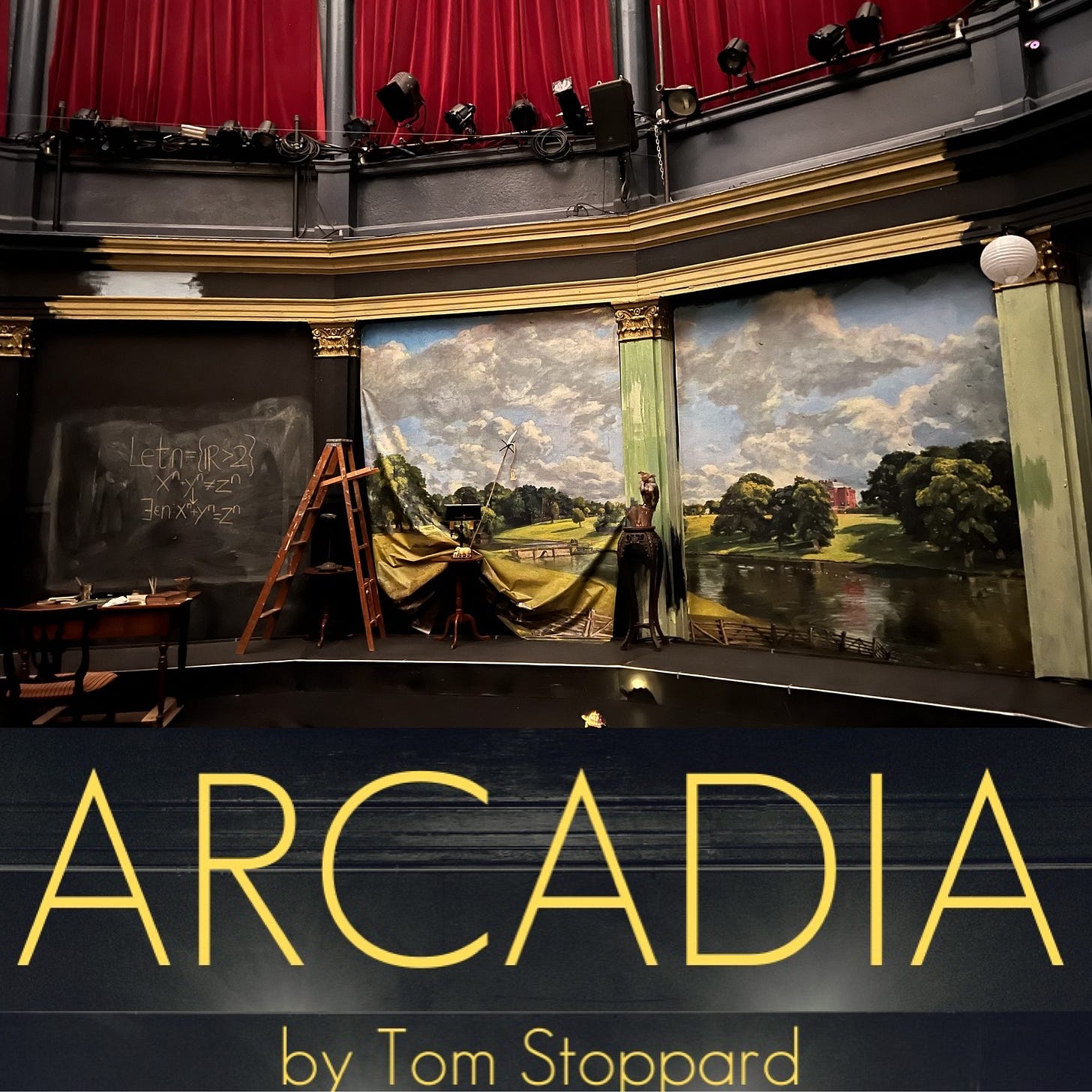

Arcadia is back in New York after a long longueur. The hyper-inventive Bedlam theater company is putting it on uptown in the Westside church where my daughter Sara has attended theater camp for years, which is disorienting for me but of no relevance to you. It actually is a lovely space for Arcadia, a domed, circular second-story rotunda with the aspect of a Renaissance lecture hall.

Something about New York has never quite agreed with Arcadia. The script’s complex bouquet loses something in the transition. Though its beauty is clearly universal — a sweet spot where science, math and metaphysics tangle deliciously around a love story or two told in different historical dimensions — Arcadia is, nevertheless, supremely British. Set in a grand English country house, its universality cannot escape its Englishness.

At least it cannot for me. Initially, I couldn’t wait for it to come to New York, which it did in 1995, under the auspices of Lincoln Center Theater. Trevor Nunn again directed, as he had in London. Where the original British company was just about the finest I have ever seen on a London stage — the great Felicity Kendal, the sublimely great Bill Nighy, Rufus Sewell, Harriet Walter, and Emma Fielding as the preternaturally precocious Regency-period mathematics prodigy, Thomasina — the American cast was also first-rate: Billy Crudup, Blair Brown, Victor Garber, Robert Sean Leonard, the late-lamented Lisa Banes, Paul Giamiatti in his Broadway debut, with Jennifer Dundas as Thomasina. Yet, much of the play’s magic seemed to dissipate in NYC (including a subsequent 2011 Broadway revival). Maybe it’s the accents, I remember thinking.

It should be a good idea that Bedlam has decided here to dispense with phony English accents altogether. But it isn’t. The prosaic American flatness of their speech renders a good deal of Arcadia’s richness flat as well. I wish it were otherwise.

As for the acting, Bedlam’s is a marvelously resourceful ensemble, witty and nimble, but rarely do they rise individually to the level demanded by Tom Stoppard’s lofty creations. The staging, by Eric Tucker, is clever and self-referential, with the audience seated where they belong for the First Act, then onstage in the Second Act, watching the actors race around the risers among our vacated chairs, tossing props to each other, to and fro, in an ingenious juggling act.

Does Arcadia need any of this artful gimmickry? I leave that to you.

Transpiring simultaneously in the early-19th and (as updated by Bedlam) our own 21st Century, Arcadia defies simple synopsis, spinning twin plots packed with seduction, intrigue, scholarly erudition and indiscretion. Lord Byron plays an offstage role in both epochs. The original showbill in London back in ’93 contained a thick insert, dense with encyclopedic explication — scientific, mathematical, horticultural. I will never forget the sight of a balcony-full of speed-reading playgoers, clinging to their seats at Intermission, voraciously scanning this insert for further edification.

They missed the point. Far beyond erudition, what Arcadia imparts exquisitely is the heartbreak of what we will never fully know — about the past or the future — and how we console ourselves for that with love, right now, if possible. This is how Tom Stoppard writes, and Arcadia, in my opinion, is his masterpiece. For this reason alone, I thank Bedlam for bringing it back. I’ll probably even go see it again. Before it’s gone again.