Liner Note #2: ARI AXELROD'S "A PLACE FOR US - A CELEBRATION OF JEWISH BROADWAY"

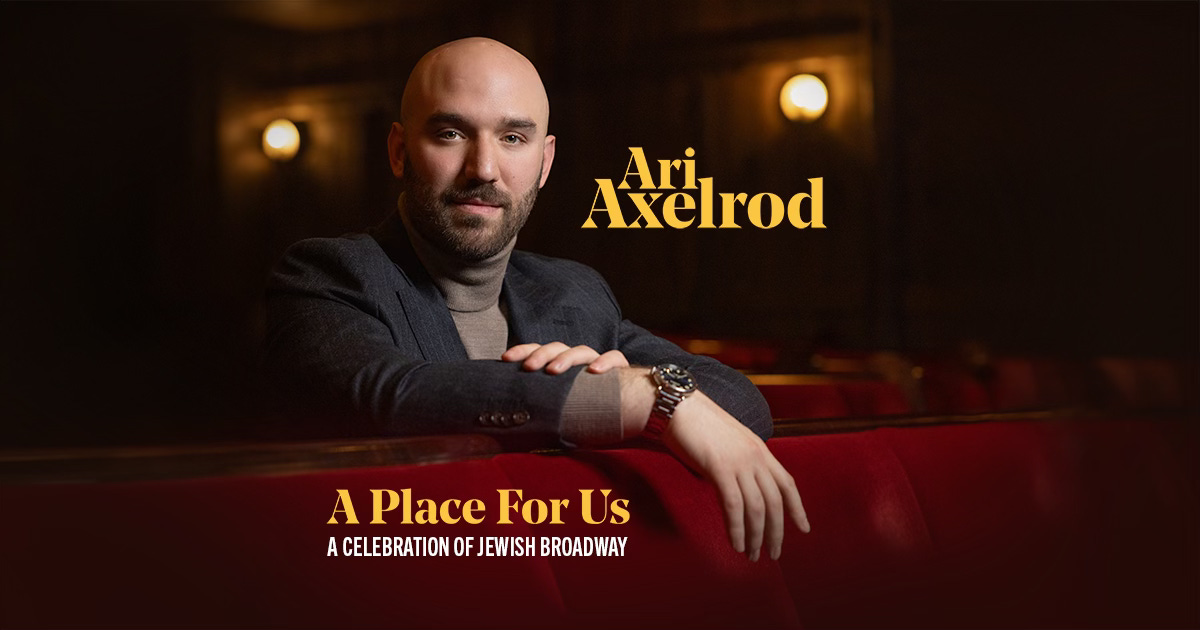

This, my second recent liner note, came out of the blue. (To read about the first, click: HERE.) Tommy Krasker, estimable owner of the PS Classics record label, reached out with an advance release — A PLACE FOR US: A Celebration of Jewish Broadway —by a singer new to me named Ari Axelrod, and asked for some liner notes, quick!

Having endured a long-ago trudge through yeshiva-dom that rendered me altogether a-religious, I still felt almost over-qualified for this job. A PLACE FOR US: A Celebration of Jewish Broadway cuts right through the conflicted junction between my Jewish and Broadway selves. I know far too much about the former, while also appreciating the depths of Jewish tradition underpinning the latter.

Here is the note I wrote:

Organized religion has inspired all kinds of exceptional music from creative spirits determined to escape its strictures. In American Judaism’s case, much of that musical counterpoint was birthed on and around Broadway.

Ari Axelrod gives full voice to the vibrant spectrum of this music he calls “Jewish Broadway.” His song choices and, especially, his song juxtapositions, not only lay out the history of a fervently hybrid music, they often illuminate the Judaic antecedents within these melodies.

It is quite Talmudic — the question and answer, call and response woven into these tracks. The arrangements, by Mike Stapleton, with an assist from Larry Yurman, whisper the songs’ secrets — the liturgical backstory of some, the Yiddishe backstory of others. The album is an immersion, like a Mikvah (Jewish ritual bath); a dip into swirling cultural waters.

A multi-award-winning cabaret artist from Ann Arbor, Michigan, whose great-grandfather was a cantor in Odessa, Ukraine, Ari Axelrod went to Hebrew day school, became obsessed with musical theater in high school and graduated Webster University’s Conservatory of Theatre Arts in St. Louis. A couple of years later, in 2018, he was invited to deliver a talk at a Michigan university on the connections between Judaism and Broadway. A PLACE FOR US evolved from that lecture into a response to rekindled anti-Semitism around the world; a celebration of Jewish survival and defiant Jewish achievement.

All of the songwriters represented here, with one notable exception, probably went to synagogue with some regularity at some point in their lives. Synagogue sounds permeate their music, to greater and lesser degrees, reworked and deconsecrated, while their lyrics sing of love, life, and faith — usually in something or someone other than God.

Jewish identity is not a direct concern for most of these thoroughly assimilated songwriters. Their songs were written for specific dramatic moments in Broadway shows, or simply for the marketplace. That they nonetheless echo a vast Diaspora history is not even an afterthought. It is simply inescapable.

The first song, Migratory V, is, in fact, a song about God. It could not, however, be more ecumenical; a soaring speculation about humanity, divinity and their unity, written by a Jewish Tony Award-winning composer named Adam Guettel, who just happens to be the grandson of Richard Rodgers (another contributor to this album). Migratory V was composed for Guettel’s theatrical song cycle, Myths and Hymns, a meditation on Greek Mythology and hymns from a 19th Century church hymnal that Guettel found in a thrift shop. Ari Axelrod nevertheless imbues it with a wholly Jewish yearning for transcendence.

He then addresses the Hatikvah, Israel’s deeply moving national anthem, written by the Moldavian-born Shmuel Cohen in the late-19th Century as a setting for a popular poem "Tikvatenu" (“Our Hope”), by Naftali Herz Imber. The song became the unofficial national anthem of Israel by acclimation long before there was anything resembling an actual Jewish State. Axelrod does not sing it initially but rather intertwines it instrumentally through an extraordinary song called Hope, written by the prolific Broadway composer Jason Robert Brown the morning after the shattering Presidential election results of 2016. (Yes, sometimes we are forced to renew hope).

Axelrod next tackles Jewish Broadway standard-bearers Stephen Sondheim, Jerry Herman and Cole Porter, the only “goy” in this pantheon, who once famously confided to Noel Coward, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart over a 1926 dinner in Venice that he had figured out the secret to writing hits: “I’ll write Jewish tunes,” said Porter. And he did, composing "fragesh" melodies that deployed ancient Jewish proto-blue notes — a lowered third at just the right moment — creating affirming major key melodies with minor key overtones. It was a music of longing, the music of a people who — as the conductor Michael Tilson Thomas has observed — “once upon a time heard God's voice and are still waiting to hear it again.” Ari Axelrod underlines these “krekhtsen” (moaning) melodies by framing Porter’s You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To (written for the 1943 film Something to Shout About) and So in Love (from Kiss Me Kate) around Papirosin — the 1920s Yiddish theater classic by Herman Yablokoff, whose melody would appear to have influenced Cole Porter. A lot.

A three-song medley from Jerry Herman’s first Broadway musical, Milk and Honey, ensues. An agitprop rom-com about husband-hunting American tourists in Israel, Milk and Honey, produced in 1961, spotlights Herman’s quintessentially optimistic romanticism as a Broadway composer. It also captured a very optimistic moment in time, just after the 1960 release of the movie Exodus, when Israel gleamed as a heroically romanticized new nation.

Everybody Says Don’t, from Anyone Can Whistle, and Children Will Listen, from Into the Woods, are two of Stephen Sondheim’s most potent lesson songs. Each imparts a message that is in no way inherently Jewish, but in the context of this album resounds like an admonition from one Jewish generation to the next: Never accept the restrictions of prejudice on what you can achieve, Everybody Says Don’t would seem to insist. And, as paired here with South Pacific’s Carefully Taught — Broadway’s original anti-racism song, by Sondheim’s mentor, Oscar Hammerstein, writing with Richard Rodgers — Children Will Listen becomes a warning about the teaching of prejudice itself.

Axelrod follows these lessons with a lyrical Some Enchanted Evening, also from South Pacific, of course, and an ebullient Shy, written by Richard Rodgers’ daughter (and Adam Guettel’s mother), Mary Rodgers, with lyricist Marshall Barer, for their lovely early-60s musical Once Upon a Mattress.

Corner of the Sky, from Pippin, introduces into the Ari Axelrod fold composer/lyricist Stephen Schwartz — the “kid” in the Jewish Broadway family when he wrote Pippin in 1971, but now a sage among us. A song of fervent yearning for a place in this world, Corner of the Sky aptly segues into the stirring God Knows Where, a virtual documentary-in-song that traces the tumultuous Jewish immigrant journey from “God knows where to God knows where,” written by the contemporary composer Daniel Cainer.

Miracle of Miracles carries Ari Axelrod back to the beginning of this journey, the Pale of Settlement — Russia’s borderless wasteland where Jews were ruthlessly forced to live for more than a century — and the Broadway musical that immortalized Jewish life there, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick’s Fiddler on the Roof. Sung by a penniless tailor in celebration of his own small victory in finding love and happiness, the song sings of the simple joy of survival.

George and Ira Gershwin, the bards of Manhattan sophistication and modernity in the Roaring Twenties, grew up on the Lower Eastside in an impious Jewish family. Evidence that the Gershwin boys’ genius was partly ignited in the Eldridge Street Synagogue (where the Gershwin family were members) is provided here via a clear through-line drawn by Ari Axelrod from the ancient Judaic “trop” (sacred melody) for the Torah Blessings and George Gershwin’s deployment of that trop in his indelible It Ain’t Necessarily So; a deliriously sacrilegious gospel anthem sung by the drug-dealing Sportin’ Life in Gershwin’s’ grand opera Porgy and Bess.

Kurt Weill escaped Hitler’s Berlin to Paris in 1933, before fleeing in 1935 to New York City. There, in 1949, he wrote Lost in the Stars, a Broadway musical about South African apartheid, adapted from the book Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton, with lyrics by the playwright Maxwell Anderson. Weill’s majestic title song captures the wilderness of life in a world gone dark and Godless, just “lost out here in the stars,” searching for sanctuary.

There are no Jews in West Side Story but the show’s creators — Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Jerome Robbins and Arthur Laurents — were all Jewish, and the original conception for the show was, in fact, for the Romeo and Juliet-like leads and their respective families to be Jewish and Irish Catholic antagonists on the Lower Eastside. Virtually any song from this magnificent show would have a place here, but Ari Axelrod chooses to contrast the bebop-dangerous Cool with the refuge of Somewhere.

This brings him, almost inevitably, to Bring Him Home, Claude-Michel Schönberg, Alain Boublil & Herbert Kretzmer’s heartfelt plea for release and return, from Les Misérables. The faces of Israeli hostages plastered on city walls and light posts loom up in the plaintive wake of Bring Him Home, shadowed by the faces of Gazans displaced and destroyed by war.

Harold Arluck and Isadore Hochberg — under their Americanized names, Harold Arlen and “Yip” Harburg — were one of Jewish Broadway (and Hollywood)’s greatest songwriting teams, from “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” onward. Ari Axelrod brings A Place for Us to a close with a pairing of Harburg’s more obscure and deeply bittersweet lyrics. Adrift on a Star — from The Happiest Girl in the World, a Broadway musical loosely adapted from Aristophanes’ Lysistrata and composed from melodies by the German-born French operetta master Jacques Offenbach (also Jewish) — ran for a brief 98 performances in 1961. Silent Spring was a very late Arlen and Harburg collaboration, written for their friend Lena Horne’s politically engaged 1963 album Here's Lena-Now! — the song’s title and temperament derived from Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book published that same year about impending environmental disaster.

The two songs would seem to echo Adam Guettel’s opener for this album, Migratory V, though written more than 30 years earlier. The desperate resignation in Ari Axelrod’s voice is wistful; the reverberations, infinite.