EVER AFTER (slated soon to hit the streets) is dedicated to my daughters, Lea and Sara, and to the memory of my friend Jonathan Larson. The 25 year anniversary of the opening of Rent and the death of its author snuck up on me recently. I hadn't been keeping count. Jonathan died on January 25, 1996, right after returning home from the dress rehearsal for his long aborning rock opera at New York Theatre Workshop. An aortic aneurism tore open his heart as he brewed a late-night cup of tea in his kitchen.

New York Theatre Workshop commemorated Rent's birth and Jon's death in a Zoomed fundraising evening that I clicked into a week or so ago, with Lea beside me. I expected to find a screenful of Zoom boxes teeming with age-advanced faces like my own. I did find those boxed faces, but they soon gave way to a documentary film about Jonathan Larson, Rent and NYTW that, to my stupefaction, opened with my own voice speaking, and Jonathan’s.

"Papa! Papa! That's you," Lea began screaming, before I'd fully digested this myself.

In near staccato comprehension, I recognized what I was hearing, saw in my mind's eye the two of us sprawled in Jon's living room jawing into my tape recorder so many years ago, and burst into tears.

I just didn’t see it coming.

Jonathan Larson and I first met in a manner that, with every passing year, seems more like fiction. The date was June 10, 1992. I was seated in Carnegie Hall anticipating the imminent commencement of "Sondheim: A Celebration," a tribute concert shimmering with celebrity and massive orchestral accompaniment, to be broadcast on PBS. My seat was a scant two rows from the stage, so close I had to tip my head up to see. The supplier of this extraordinary vantage was Mr. Sondheim himself, whom I knew just well enough to have asked for help getting in. His office had supplied me with a single ticket.

A stranger roughly my own age materialized suddenly to my right and entered my aisle, squeezing past and dropping down in the seat beside me. He had a pallid, earnest face and wavy, earnest hair; stroked straight up on his head. Our expressions, I figure, were mutually, fearfully enthusiastic. Two social climbers crashing the swank seats. Row B.

Where I wore my tuxedo very carefully that night, this guy flaunted a mismatch of informal formals; attention-grabbing, threadbare-shrewd, thrift shop-vintage — the green thread in the blue weave of the vintage plaid of his sport coat, the wry twist of his bolo tie against the worn white of his shirt, the too-sharp toes of his laced brogans and the peeling tuxedo stripe of his slacks.

The guy, in that get-up, glanced, then grinned at me, a sideways grin that seemed to say: I know I don't know you, buddy, but we're going to talk now and you won't be sorry either. His first words were a shared confidence framed as a question.

“How'd you get your seat?”

Surely, I didn't mind answering that one. "Sondheim,” I said, as modestly as I could.

I watched the stranger's eyes widen, literally; an authentically childlike and extremely characteristic expression, I would learn. The grin broadened, ear-to-ear, big jug ears, I noticed, couldn't help noticing.

“Me too,” he said.

And we were friends.

“I write musicals,” Jonathan told me within moments.

"No kidding," I said.

At the intermission, over champagne — my treat — he said it again: “I’m writing this musical.”

"What musical?” I inquired dutifully.

“A rock opera," he replied. "No don’t say it. I know. But somebody has to make rock n’ roll work again in a musical,” he insisted, an ongoing inner debate resumed, it seemed. He took a slug from his plastic flute. “Me.”

The mob in evening clothes with their flutes everywhere crowding the Carnegie Hall bar remained oblivious. Yet, I like to think all of them at that moment joined Jonathan in a gulp of overpriced champagne.

Some nights later, I descended from the upper-Westside to lower Greenwich Street, where noir-quality desolation framed the four-story sloping wreck of a building that Jon had directed me to. No intercom, no buzzer, no numbers for an address. Was this even the right doorway? Then a face appeared at a high window and a link of keys sailed down to the pavement.

Inside, pocked linoleum stairs were all there seemed to be of the place, as I climbed: one dank landing, two...

Just short of the roof, though, a scarred steel door groaned open off the final darkened stairwell and there was Jonathan, backlit against a large, surprisingly inviting kitchen. Sadly, I can’t think of it now without picturing him crumpled motionless on the ill-carpeted floor, but that night this room reassured me: dangling pots, grandmotherly-ruffled sink stand, a teetering dinette table that did bespeak tea sipped late at night.

There was no mistaking Jonathan's feelings about the place. It's brazen tatteredness pleased hell out of him. The claw-foot bathtub mounted on blocks centerstage. The peeling stickers from every imaginable promotional or kiddy source pressed onto every wall surface, as wallpaper.

From the kitchen, Jonathan squeezed me down a corridor into the joint’s nominal living room — blanket-draped, sofa-like divan along one wall, pallet-shaped, beatnik-tiled, coffee table before it — but more clearly his studio, with lots of electronic hardware befitting a composer of “rock opera.” Two windows faced Greenwich Street. To their immediate left, Jonathan's narrow bedroom did too — mattress; bookcase of boards stacked on milk cartons heaped with dust-riven volumes; an enfeebled dresser, purple paint-swiped, clinging like a drunk to one wall.

“Nice,” I muttered, following him back into the studio/living room.

“Thanks,” Jonathan beamed.

What I found nifty was the fashionable grunge this unfashionable “musical theater composer” draped himself in. Sploshing around in work boots, fatigue pants, open work shirt over a faded tee, he looked like a roadie; patching chords and lugging plugs, preparing to “play” me his new musical. Heading downtown this night, my thoughts had run, admittedly, more toward George Gershwin at a baby grand regaling parties full of smart friends with new work. In Gershwin's place, Jonathan would first have to conduct a sound check.

He dragged over an impossible cast iron and canvas butterfly chair and helped me into it, spotting me carefully between two imposing speakers.

I felt I ought to strap in.

The more excited Jon got, the faster he spoke, his voice growing more and more muted, though, as if in awe of what he found himself saying. Thus, chattering in a near monotone of just contained exuberance, he moved about the room, switching off lamps as he laid out his musical with bare-ass naked pride.

“It’s really La Boheme,” he noted, putting the last light out, then said: “Only it's not.”

He paused. “You like La Boheme?”

“Sure,” I said.

He swooped into a chair alongside me, the only illumination now from sound equipment meters and the street. “It's called...” and Jonathan uttered that one word title most everyone today knows, everywhere seemingly, internationally, incredibly.

"Rent."

I wasn’t quite sure I’d heard right.

“All the characters are East Village kinda club kids,” Jonathan said, pulling a couple of cassettes from an open wood wall tray. "Some are H.I.V.-positive.” He glanced over. “Most.”

I winced.

"I know.” Jonathan said, moving closer to the tape deck and angling his chair right at me. “But so many people I know are.”

He handed me a script.

“You can follow here. Say stop, if you get lost. You ready?”

And before I could say anything else, Jonathan hit the play button — that title again, one word, like a fanfare, the last word out of his mouth.

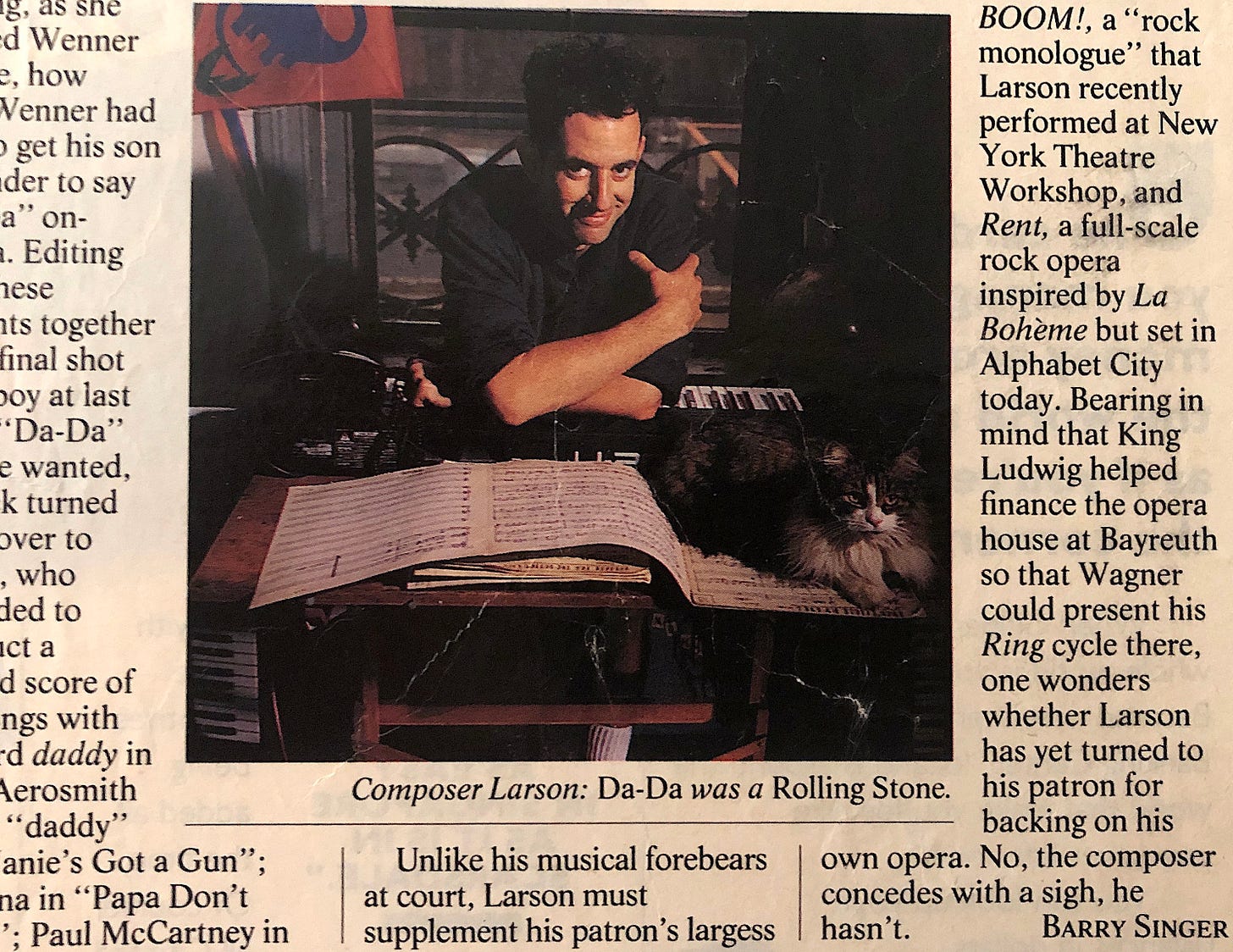

He mentioned a money gig that night, or maybe it was another night soon after, a crazy job he’d landed “scoring” home movies for Jann Wenner, the founder and publisher of Rolling Stone magazine. Fabulous, I thought, and decided to try persuading my editor at New York magazine, where I then wrote, to let me turn in a piece on Jonathan Larson.

No-one had yet written a word about Jonathan, that I know of. The interview was a gas for both of us, but a defining moment for him, which I didn’t fully grasp at the time. The cassette from it, I guess, I later copied for his family.

I still have mine, I’m sure, somewhere. Last week I heard it again, for just a moment.