"PoPsie" & SON

FOR MICHAEL RANDOLPH

Thirty-two years ago this month, my friend Vince Giordano brought me to the doorstep of the jazz photo collector Frank Driggs out in Flatlands, Brooklyn. Frank invited us in and we together descended his basement stairs to browse the finest assemblage of jazz photographs in the world, heaped in file cabinets beside Frank's boiler. It was there that I discovered "PoPsie" Randolph, the Weegee of the music scene.

"Who took this one?" I kept asking Frank, lingering over stunning shots of Miles Davis, then Dizzy Gillespie with John Coltrane, then Sarah Vaughan.

"PoPsie," he kept answering. "PoPsie took that one. PoPsie."

At first I wasn't sure I'd heard him right. "PoPsie?"

"Yeah.”

"Who the hell is PoPsie?" I finally asked.

"PoPsie Randolph," Frank answered plainly. "PoPsie was a press agent's dream because he worked cheap and he worked quick. He shot on the fly at gigs, and he shot commercial portraits, eight-by-ten glossies, head-shots."

This last quote wound up in a Talk of the Town piece that I ultimately wrote for the New Yorker about Frank and my visit to his collection in 1990. (You can read it: HERE.) My long, late night in Frank's basement inspired me in many directions. It elevated my inchoate adoration of jazz photographs into a new realm: pursuing the actual photographers who shot them. It led me to curate two exhibitions at my bookstore, Chartwell Booksellers, of "Jazz Photographs from the Frank Driggs Collection." When I began writing for the New York Times Magazine a few years later, I successfully pitched a piece celebrating jazz photographers for a pending All-Jazz issue. When the piece got killed because the magazine editors decided the issue should only be about living (and preferably young) jazz personalities (too many of the subjects in my story were dead), I took my article over to the Times' Arts and Leisure section, which published it one ensuing Sunday in a gorgeous double spread. (You can read that: HERE).

The Times story led me to hunt down just about all of the greatest jazz photographers still living. I interviewed William P. Gottlieb, Chuck Stewart, Herman Leonard, William Claxton, Lee Tanner and many more for my piece. Later, I curated photo exhibits at Chartwell for each of them.

Unfortunately, I did not meet PoPsie Randolph because he was already gone in 1997. My obsession with his work, however, never abated. I mounted two PoPsie shows at Chartwell and learned as much as I could about this mysterious lens genius who had largely worked out of the trunk of his car. The more I learned, the better the story got. PoPsie, I found out, was born William Sezenias to Greek immigrant parents in Manhattan in 1920, and had dropped out of school in the eighth grade. Scuffling for money during the Depression, he'd gone to work as a “towel boy” at a midtown bordello frequented by musicians like Benny Goodman. Goodman, who famously called fellow jazz musicians "Pops" when he couldn't remember their names, very well may have supplied young "PoPsie" with his nickname in the diminutive. BG definitely hired the kid as a “roadie” (or “band boy” in the parlance of the age), to set up the Goodman band’s instruments.

PoPsie took the surname Randolph off a Chicago Street sign, in lieu of laboriously spelling out his Greek moniker for a hotel clerk while booking rooms as road manager for the Goodman band. It was Benny Goodman who gave PoPsie Randolph his first professional caliber camera (as a wedding present) and bankrolled him as a professional photographer. PoPsie apparently liked to take pictures of the band and BG liked the pictures PoPsie took. He was not alone. One of the musicians PoPsie followed around and photographed was a young vocalist with the Harry James orchestra, by way of Hoboken, New Jersey, named Frank Sinatra. Sinatra let PoPsie trail him, photographically documenting the kid singer’s relatively fleeting time with Harry James and then Tommy Dorsey. PoPsie also miraculously captured what you might call Sinatra’s immaculate conception. On December 30, 1942, "The Voice" officially launched his solo career with an appearance at the Paramount Theater in Times Square, opening for the Benny Goodman Orchestra. PoPsie was there with his camera. So was Jack Benny, who introduced Sinatra that day and recalled the resulting response of 5,000 berserk, mostly female, audience members: “I thought the goddamned building was going to cave in.”

Goodman put it even more succinctly, as the sonic “Frankie!” roar hit him from behind for the first time on the Paramount stage: “What the fuck was that?”

PoPsie Randolph managed to grab the only known pictures of this seismic historic moment because he was in the right place at the right time — as he would be again and again in a photo-taking career that encompassed four decades and every important pop music personality, from swing to rock and roll; Goodman, Ellington, Basie and Sinatra, to Elvis, the Beatles at the Plaza, the Stones strolling in Times Square, the Velvet Underground in the studio, and Jimi Hendrix, whom PoPsie captured playing his right-handed guitar upside-down, as a leftie, in the soul singer Wilson Pickett’s backup band in 1966.

I curated my first all-PoPsie Randolph exhibition at Chartwell Booksellers in 2007. It was an extraordinary success. One day during the show's second month, a tall, lean gentleman ambled into the store and asked how PoPsie's photographs were selling. Very well, I answered. "I can't say I'm thrilled to hear that," the stranger retorted, “my name is Michael Randolph and those are my father's pictures."

Frank Driggs, in his basement, had told me he'd been offered the opportunity to buy PoPsie's "stuff" — his entire 100,000-plus cache of negatives — by one of PoPsie's sons after PoPsie died, from cancer, at the age of 57 in 1978. All he could afford to buy, Frank said, was 30,000 of those negatives.

Clearly, Michael Randolph was not the brother who'd made that sale. When I explained to him where my PoPsie prints had come from, he was not placated.

Michael’s innate sweetness, though — a quality many people also had used to describe his father — instantly overcame Michael’s inherent objections to how his pop's pics had come to line my walls. Michael so loved how those pictures looked up there that he quickly suggested I remount my PoPsie show with prints from his own extensive family holdings.

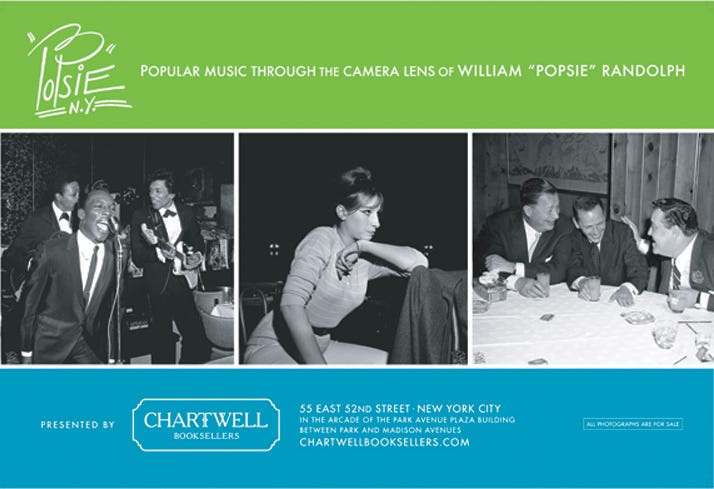

I agreed, and a friendship was born. We redeployed the new show to launch Mike’s new book about his dad: "PoPsie" N.Y: Popular Music Through The Camera Lens of William "PoPsie" Randolph, a first-rate catalogue of PoPsie's greatest images that remains in print today.

No-one got a bigger kick out of PoPsie pictures than his son Michael, who later asked me to write an introduction to another book he was putting together collecting his father's early Sinatra images; FRANK SINATRA NEW YORK, NY 1939-1956. I was proud to accept.

I can't say what made me think of Michael Randolph and his father just now. I simply find it’s time to write something about the both of them. So, here's to you, Mike. And, to PoPsie.