RE-WRITING IN BLACK & WHITE

When I was writing BLACK AND BLUE: The Life and Lyrics of Andy Razaf in the 1980s (finally publishing the book in 1992), it did cow me at times that I was a White man attempting to write the story of a Black man. In the face of my apprehension, I reminded myself that Razaf — the greatest Black lyricist of what is now referred to as the Golden Age of American Popular Song, and one of the great American song lyricists of any race, ever — had been ignored even in his own lifetime. No one knew his story. No one had really attempted to tell his story. And I wanted to, badly. So, by default, my racial reservations receded (without subsiding), and I pressed on.

When I finally located his widow in Los Angeles and told her I wanted to write her late-husband’s biography, she retorted that I was: “too young, too Jewish, and too White.” She was holding out for Alex Haley, Andy’s widow insisted, whose book, Roots, had recently been made into a ratings-record-setting television mini-series. I pointed out that, though this was a nice idea, Alex Haley had no interest in writing Andy Razaf’s biography. I did.

In the end, Mrs. Razaf, who was White, came to be persuaded by the legendary record producer, John Hammond, who was also White, to settle for the White Jewish kid. Hammond and I had met over the course of my early research and, hearing of my predicament, this lifelong champion of Black music — who had discovered, signed and recorded Count Basie, Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin (to say nothing of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen) — picked up the phone and called Andy Razaf’s widow on my behalf. His mere name on the other end of the line seems to have convinced her.

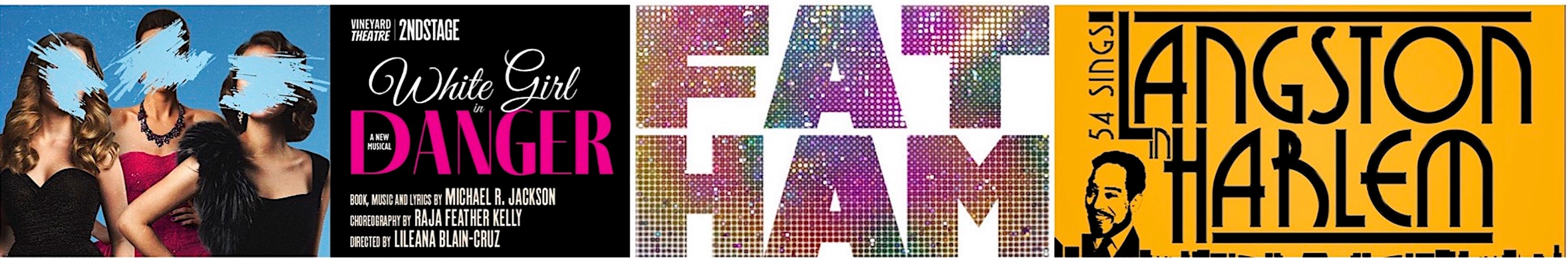

Over the course of this theater season, I’ve attended three different shows that have rocketed my thoughts back to the genesis of BLACK AND BLUE and my shifting feelings ever since about who should tell who’s story:

Fat Ham, by James Ijames — a lacerating and uproarious retelling of Hamlet through the eyes of a queer young Black male, as his suburban family of color circles each other around their backyard barbeque pit.

White Girl in Danger, by Michael R. Jackson — a kick-ass follow-up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning musical, A Strange Loop; another outrageous work about outrage and race.

Langston in Harlem — a music-theater piece constructed from the poetry of Langston Hughes, that played in-concert for one night only at 54 Below, with music and dialogue by the veteran pop songwriter Walter Marks, best-known for the 60s hit, “I’ve Gotta Be Me.”

All three of these shows grapple, in their way, with how to tell and who may tell the story of Blackness in America. Fat Ham and White Girl in Danger are both radical in their approach, while Langston in Harlem is decidedly retro. All three made me uncomfortable in wildly different ways and for wonderfully different reasons. I’m still trying to sort them out.

Fat Ham — nominated for a Best Play Tony Award this year, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize last year — audaciously appropriates William Shakespeare, the primo White playwright of them all, and his snowy Prince of Denmark, to chronicle a story of Black life and queer existence from the inside out. The language, naturalistic and utterly contemporary, is the playwright’s, of course, except when it’s not; direct quotations from Hamlet bubble to the surface like thought balloons, at critical junctures, and their dramatic power and eloquence lose nothing in the transposition. Every time they resounded, I got chills.

Fat Ham is a marvel of dramatic imagination, theatrical stagecraft and virtuosic performances, especially the sly understated work of Marcel Spears as Mr. Ijames’ protagonist, Juicy. The play is impeccably drawn (and quartered), a triumph, and a gas, by turns hilarious and excruciating in its truth telling.

But what about the other way round, I found myself wondering? Could Shakespeare appropriate Black Experience and make it work in a play? Well, he did, whether you consider Othello a masterpiece or a misadventure. Shakespeare’s power of empathy was collosal — he managed to get under the skin of an astonishing array of humans, including, somehow, a Jew named Shylock, despite never having laid eyes on an actual Jew in his life. Similarly, he conjured a Moorish military commander, without condescension. Othello is not an underling. He is the guy giving the orders. Yes, a playwright of color writing in Shakespeare’s time (had that been possible) would have composed a more expansively authentic Othello, from within. Did that preclude Shakespeare’s right to write his own? Not in my opinion. It is the same literary right that has brought us the divine reimaginitive voice of James Ijames in Fat Ham.

White Girl in Danger (which recently closed at Second Stage theater) delivers us up to a world not merely reimagined but an alternate universe. The setting is “Allwhite,” a soap opera land that is nevertheless real, where the foreground characters are all white and the background characters are all “Blackgrounds.” The high school world that they inhabit is a closed racist television set where the white girls are always in danger — of addiction, eating disorders or beatings at the hands of their hyper-macho boyfriends (when they’s not being discovered murdered in the woods). The Blackgrounds are all adult menials who work at the school, or black students with no storyline of their own. One of them, named Keesha, wants in.

White Girl in Danger is essentially Keesha’s story, as she demands “her own story.” The kaleidoscopic narrative is far too complex and self-referential to summarize or even completely follow. The all-powerful deity of “Allwhite” literally is “The Allwhite Writer,” who is everywhere and determines all fates, white and black.

…And it’s a musical, with a terrifically catchy original score by Mr. Jackson; a potboiler of 80s, 90s and early-aughts pop, shot through with threnodies of theme songs from soap operas and teen-TV .

I loved White Girl in Danger in all of its digressive, overly discurssive, seemingly endless, raging three-hours-plus (with intermission). ‘Why not cut this?’ I kept thinking, but finally realized that this script cannot be cut by anyone other than the author. White Girl in Danger is Michael R. Jackson’s vision and Michael R. Jackson’s voice. It is not mine or yours. It cannot be reimagined or rewritten by anyone other than “The Allwhite Writer,” who, I can tell you now, turns out to be Black. Mr. Jackson demolishes Black and White “woke” culture in White Girl in Danger, alongside the racist White world we live in. His final plea is for “Black stories” told by Black writers, but I somehow still felt he was also embracing me.

Which leaves Langston in Harlem to puzzle over, an awkward hybrid that was first produced, fully-staged, in 2010 at Urban Stages, off-Broadway, but was reconstituted (and reimagined) by Classical Theatre of Harlem, for a one-night concert at 54 Below some weeks ago. This production featured a stellar cast of spectacular voices, led by Brandon Victor Dixon (as Langston) and Brenda Braxton, who gave full-throated affirmation to Langston in Harlem’s sporadically soulful score. Langston Hughes, interestingly enough, was a close friend of Andy Razaf’s. The two poets shared their work with each other (Andy only became a lyricist because becoming a black poet professionally had no financial future). Hughes wrote an introduction to an Andy Razaf poetry collection (in Andy’s lifetime) that was never ultimately published. The subterranean fissures of their shared racial frustations ran deep.

There was something awfully melodramatic, to me, about Walter Marks’ musical settings of Hughes’ poetry, a sense of music hyping up Langston’s words, rather than collaborating with them. Marks, who is White (like me), also wrote interstitial dialogue connecting the songs that felt positively antediluvian, hyperbolically looking over Langston’s shoulder, rather than getting into his bones. Simmerings about Hughes’ closeted queerness and his mama’s disapproval, while not historically inaccurate, felt overwrought and secondhand in the sensationalistic way that old 50s noir films about homosexuals, Negroes and drugs once did. I have no doubt that Mr. Marks wrote this piece with nothing but love, and I appreciated 54 Below bringing Langston in Harlem to its intimate nightclub stage (that could barely contain it). Nevertheless, there are better ways to explore the words and music of Langston Hughes’ heart and mind than this creaky vehicle, and writers better equipped to do it. I’m betting those betters are still to come.