T. & Me: Lost & Found

I seem to have taken the summer off, for other writing, leaving this piece too long aborning. In the drawn out interim, though, the story has turned slightly prescient. Utterly unintentional, but there you go.

My original notion was to simply share my pandemic reconnection with a dear and admired old friend, the poet-novelist-dramatist-critic-journalist-librettist and sage, Thulani Davis. Recently, however, it was announced that for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf will be coming back to Broadway this season. Suddenly, my relinking with Ms. T. has more than solely personal resonance.

for colored girls gave me my friendship with Thulani, however circuitously. Many years ago (many!...1977), I found myself felled by for colored girls, Ntozake Shange's staggering "choreopoem" — as she called it; stopped cold by the show's all-female cast of seven (including Ms. Shange herself), who gave voice and shape to a kind of theater I'd never seen before. The show's knife-edge-blend of words, music and movement laid bare much that had seemed previously inexpressible about the pain of existence and the exultation of community for women of color. Like so many inducted into these shared secrets as an audience member, I remember sitting in the Booth Theater when it was over and thinking: I want more of this.

I went looking for Ms. Shange and her ladies, and found them just a few months later down at the Public Theater, where I'd missed for colored girls in its initial premiere, before the move to Broadway. Ms. Shange had a new piece, at the Public's LuEster T. Mertz Hall, called a photograph: a study in cruelty, about a male photographer and the three women in his life he psycho-emotionally bashes, as per the play's subtitle. The work was a more (and less) literal riff on for colored girls' transcendent skewering of misogynistic males, but it also boasted a kick-ass band of young jazz lions, led by Ms. Shange's then-husband, the titanic tenor saxophonist David Murray.

a photograph hit the Public in December 1977, three months after for colored girls opened on Broadway. Sunday nights throughout its roughly month-long run, a raucous revue called Where the Mississippi Meets the Amazon was also presented at the "Public Theater Cabaret" (precursor, of course, to what is now Joe's Pub ). It featured, and was co-written by, Ms. Shange and her poetry-writing consort going back to their days together as Barnard College students, Thulani Davis, riffing in tandem with a third grand poetess, out of San Francisco (where Thulani also was then based), the extraordinary Jessica Hagedorn.

Once again I was enthralled by the sense of improvised music (let's call it jazz) and improvised poetry (let's call it poetic improvisation) that these women and a band of exceptional, young avant garde musicians (again fronted by Mr. Murray) generated. The whole business was more overtly "old school" in its theatricality, with the ladies dubbing themselves "The Satin Sisters," outfitted in glam 1930s gowns, while the band was in wide-lapeled suits, and more directly part of the stage interaction. The sense of ferment was overpowering. No one on any given night knew where the words and the music might lead.

I decided I would write about this new "movement" (as it appeared to me) of female poets of color and jazz poets of color, in collaboration. I pitched the idea to the editors at Rolling Stone magazine, where I then worked as a peon, and they, well... humored me. Thus encouraged, I went about meeting Ms. Shange and company. In time, I wrote the piece and, in even less time, Rolling Stone passed on it, which was their mistake; they missed out on something no-one has yet fully documented. So, shame on them.

The friendships that grew out of my failed attempt at reportage nurtured me nevertheless. I spent a number of hours initially with 'Zake,' who was mercurial and not easy to know. Same went for David Murray (which is perhaps why they ultimately divorced). Both, however, did turn me on to other cutting-edge poets and players, including Murray’s fellows in what was just becoming The World Saxophone Quartet in 1978 — Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake and Hamiet Bluiett. Interviews with them and other musicians (often grabbed between sets, up multiple flights all around Manhattan, in what was then the "loft jazz scene") brought insights and other sweetness. The musician I enjoyed most was the irresistibly loquacious and philosophic Butch Morris, a Vietnam medic vet out of Northern California, whose compositional sense of group improvisation exceeded all bounds of structural imagination. ("Conductions," he called his ensemble pieces — through-improvised —which he conducted, baton and all.) Butch and I spent hours schmoozing, some of them nights that he crashed on my living room sofa. There simply wasn't real rent money in being a visionary, even in the 1970s. Butch barely complained.

Jessica Hagedorn and I immediately hit it off. Her novel, Dogeaters, a teeming Dickensian portrait of life during the Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos years in the Philippines, would win the American Book Award in 1990; I witnessed Jessica's triumph with beaming affection. I got to know Laurie Carlos, one of for colored girls’ original cast members. She was a glorious, straight-shooting pistol; a true illuminator. The choreographer Dianne McIntyre encompassed in movement everything that these poets and musicians were expressing and exploring. I spent awestruck hours at her 125th Street studio just watching her Sounds in Motion company rehearse — if an observer can dance, in my head I danced. Patricia Jones, another vastly talented poet on the scene, became one of my dearest friends, to this day; I wrote about Patricia and her artistry during my Huffington Post years.

Finally, though, there was Thulani. I was sure we first met after a Mississippi Amazon performance (the revue was extended well into May 1978), but Thulani insists it was later, at what became her one-woman show, Sweet Talk and Stray Desires, at the the Chelsea Westside Theater Center in July 1979. Certainly, I remember that night; Thulani's actors failed to appear and she called her cousin, Anthony, out of the audience to back her. I was a big fan of Anthony Davis, as a pianist and composer, and was thrilled to get to hear him impromptu. He and Thulani would go on to write the operas X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X, and Amistad, among other groundbreaking collaborations.

Thulani and I became pals. We liked the same kind of music. She'd begun writing pop music and theater reviews for the Village Voice and would soon become one of the Voice’s top drama critics and a Senior Editor. We went to see things together — music and theater and much that was in between — with plenty of drink and talk about what we'd seen, after. Thulani married Joseph Jarman, saxophonist and co-founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and was ordained a Buddhist minister, opening with Joseph their own "dojo/zendo" out of their Brooklyn home. In 1992, when her superb novel, 1959, was published, we put together a reading of it at my bookstore, Chartwell Booksellers, with members of the Jelly's Last Jam Broadway company, including the show's director, George C. Wolfe, and its stars, Gregory Hines, Tonya Pinkins and Keith David. The reading was a benefit for the Bookstore Relief Fund of Los Angeles, where riots had recently brought down a number of local black-owned enterprises, including L.A.'s most venerable bookstore, the Aquarian Bookshop. That was some evening.

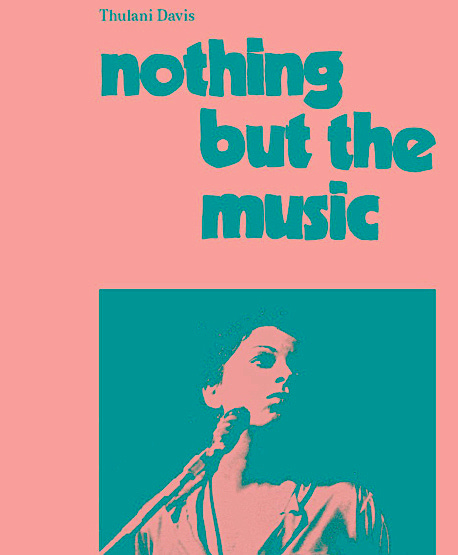

With time, Thulani and I lost touch. Her writing career took her around the world. My marriage and family took me home, where I refocused more and more on just raising my kids. Then came the pandemic, and an emailed invitation from Thulani to a Zoom book party for a new volume of her older poems: nothing but the music: Documentaries from nightclubs, dance halls & a tailor's shop in Dakar 1974-1992.

Hell yeah, I'd like to read that.

I attended the Zoom party. Turns out Thulani has, for a while now, been a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. There she was on the checkerboard screen of faces, accepting congratulations and reading poems about places she and I once knew well. In the chatbox, we quickly agreed to re-Zoom soon, just the two of us.

This is what the pandemic has done for so many people, I suspect, in the positive; it has brought them back together with loved ones — family or just companions who slipped away for a while.

Our first Zoom lasted over two hours. More followed. So much catch up, so many future projects to dissect. Then, an invitation: Thulani was doing an online event promoting her new book through A Room of One’s Own, a very fine local bookstore in Madison. Would I like to join her “in conversation?”

We talked for a solid hour, reminiscing, revisiting lost spaces and the music that we heard made in them. I believe you can still watch us if you click HERE. Some conversations are worth the wait.

Working in new

forms, stepping

outside tradition is

like taking a solo …The artist breathes

in a heap of air; the

chords, tones, and

even the structures of

his or her world and …And then in one

concentrated

moment moves

and breathes

out …The sound becomes

a shape, a dance, a

configuration of what

we know that we have

not seen or heard that

way …but still with

that sensibility that

taught the world how

to solo—solitary

yet communal,

disciplined and free.—Thulani Davis

For Ishmael Houston Jones

1982, 122nd Street, New York