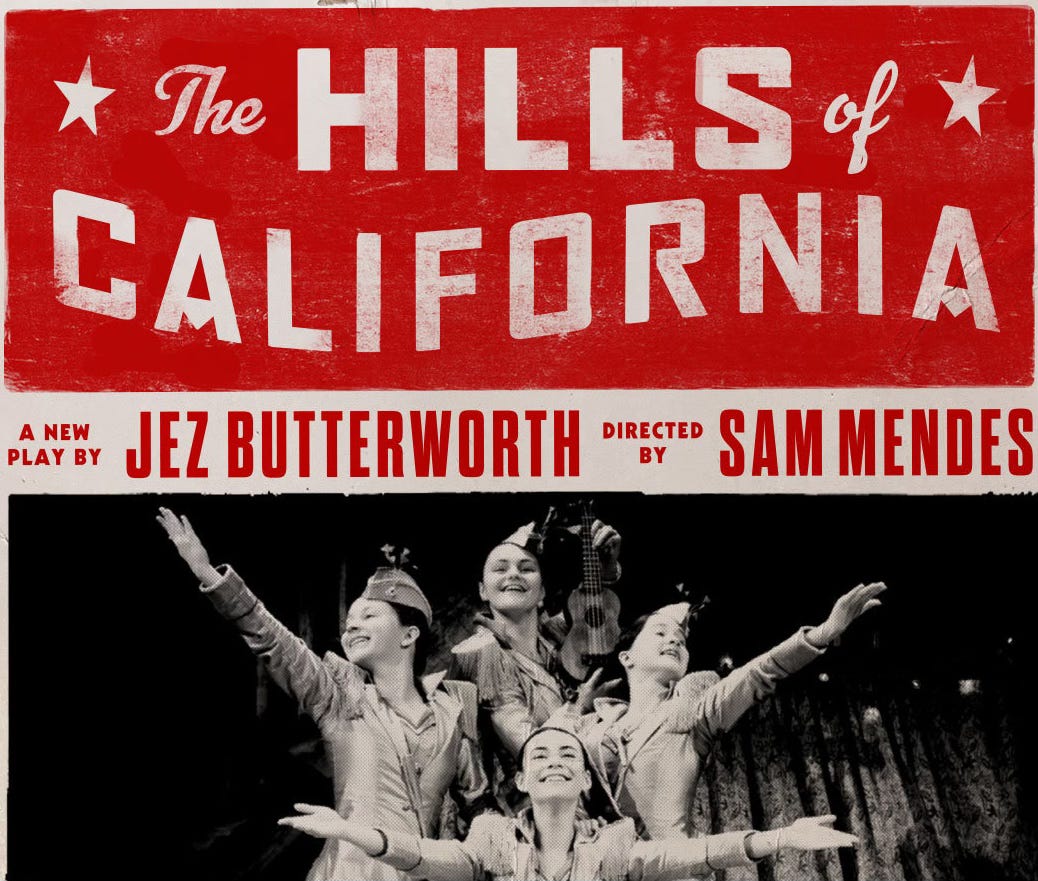

"THE HILLS OF CALIFORNIA:" Gimme Shelter

I watched The Hills of California, Jez Butterworth’s new play on Broadway, from a plethora of personal perspectives:

As a fan of Butterworth, the playwright — interested in anything he has to say.

As a lover of musicals — tickled by the close harmony the singing sisters in his play burst into periodically.

As an epicure of fine ensemble acting — savoring the meal served up by this company.

As a survivor myself — grappling with the child sexual abuse at the heart of The Hills of California.

That’s a load for one new play to both generate and absorb. The Hills of California manages this eloquently, if inefficiently at times, but, ultimately, heart-wrenchingly.

Jez Butterworth is a wild card. His theater, in my experience, feels simultaneously familiar and disquieting. The Ferryman, his 2019 Tony Award-winner about the Irish Republican Army and betrayal, was both fond and fierce. I loved it.

The Hills of California also tackles betrayal but the stakes are less starkly drawn, by intent, though the cost is clear. An unhappily loving family is the IRA of this story. The family’s codes, conventions and secrets are as ruthless and unbending as any terrorist group’s. Butterworth, as ever, is both possessed and unmoved by the human toll of it all.

The show, as you may have heard, opened earlier this year in London, directed by Sam Mendes, and was nominated for an Olivier Award as Best Play. It moved to Broadway (with unusual haste) in September.

Set in a shabby guesthouse on the outskirts of the English seaside resort Blackpool, The Hills of California is time-fluid — flowing and ebbing, to and from the Summer of 1976 and the late Spring of 1955.

Jillian, Ruby, Gloria, and an absent Joan, are the adult daughters of Veronica Webb, who is dying upstairs of cancer as the curtain rises. Veronica never comes down those stairs, but her younger self and those of her daughters — 20 years younger — soon appear. We watch them familially bounce off each other — a tenacious single mom raising her moderately talented young teen brood, Mama Rose-like, whipping them into tap-dancing Andrews Sisters imitators; “The Webb Sisters,” who she knows will be stars.

Of course, the girls both hate her and love her. Of course, the Andrews Sisters in 1955 were past their prime and irrelevant; and, of course, Veronica is single-mindedly oblivious to this. Until the arrival of an American, a slick talent agent ostensibly connected to Nat King Cole, who turns up at the guest house and is lassoed by Veronica into auditioning her kids right there in the kitchen.

An essence of cheap seduction wafts back and forth between Luther and Veronica; two promoters on the make. With the girls dancing before him in full costume, wailing “The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” Luther cuts short the audition, sardonically inquiring of Veronica if she has ever heard of Elvis Presley. She has not. He then calls out the eldest, prettiest and most talented Webb sister, young Joan, and proposes auditioning her privately. Veronica, after volunteering herself instead …accedes, handing her daughter over. Luther and Joan disappear up the stairs.

When next we see Joan, she is making an entrance for the ages — really one of the great entrances that I’ve witnessed in a lifetime of theatergoing. Night has come, the sleeping house is silent. Time has passed and Joan has not been heard from for years; gone to America. Her grownup sisters have been speculating, with conflicted degrees of envy, shame, loathing and love, whether Joan will show up from L.A. to see her mother before she dies.

An ancient broken jukebox in the parlor suddenly comes to life, alight in the dark, whirring a record into place. The record drops. The maelstrom of “Gimme Shelter,” The Rolling Stones, resounds in the blackness. And then, a figure appears, her cigarette glowing, a louche female figure, draped caustically in Janis Joplin rock and roll diva rags, down to her fur-trimmed coat. The anarchic fury of “Gimme Shelter” and the Stones swirls round her as she saunters, smoking, peering into the virtually unchanged old room. It is Joan returned. And I am telling you, I could barely breathe.

Nothing that followed could top that entrance. Kudos to Sam Mendes for staging it.

If I said “Gimme Shelter” made The Hills of California for me, you might think I was minimizing the show. If I said The Hills of California made “Gimme Shelter” anew for me, you might think again.

Think again.

One further facet of this transporting coup de théâtre: The actress playing Veronica — the extraordinary Laura Donnelly, who happens to be Jez Butterworth’s life partner — also plays the prodigal Joan. I will admit that I didn’t realize this until I was home turning the pages of my Playbill hours later. Two devastating performances. Mother and daughter.

The rest of The Hills of California unfolds as a mine-clearing operation, essentially — ancient family ordnance detonated under controlled conditions. Tears, laughter, recriminations, confessions, all circle the awful question: Will Joan climb those stairs to her mom’s room for a final goodbye?

Can a child ever forgive their sexual abuse?

I won’t tell.