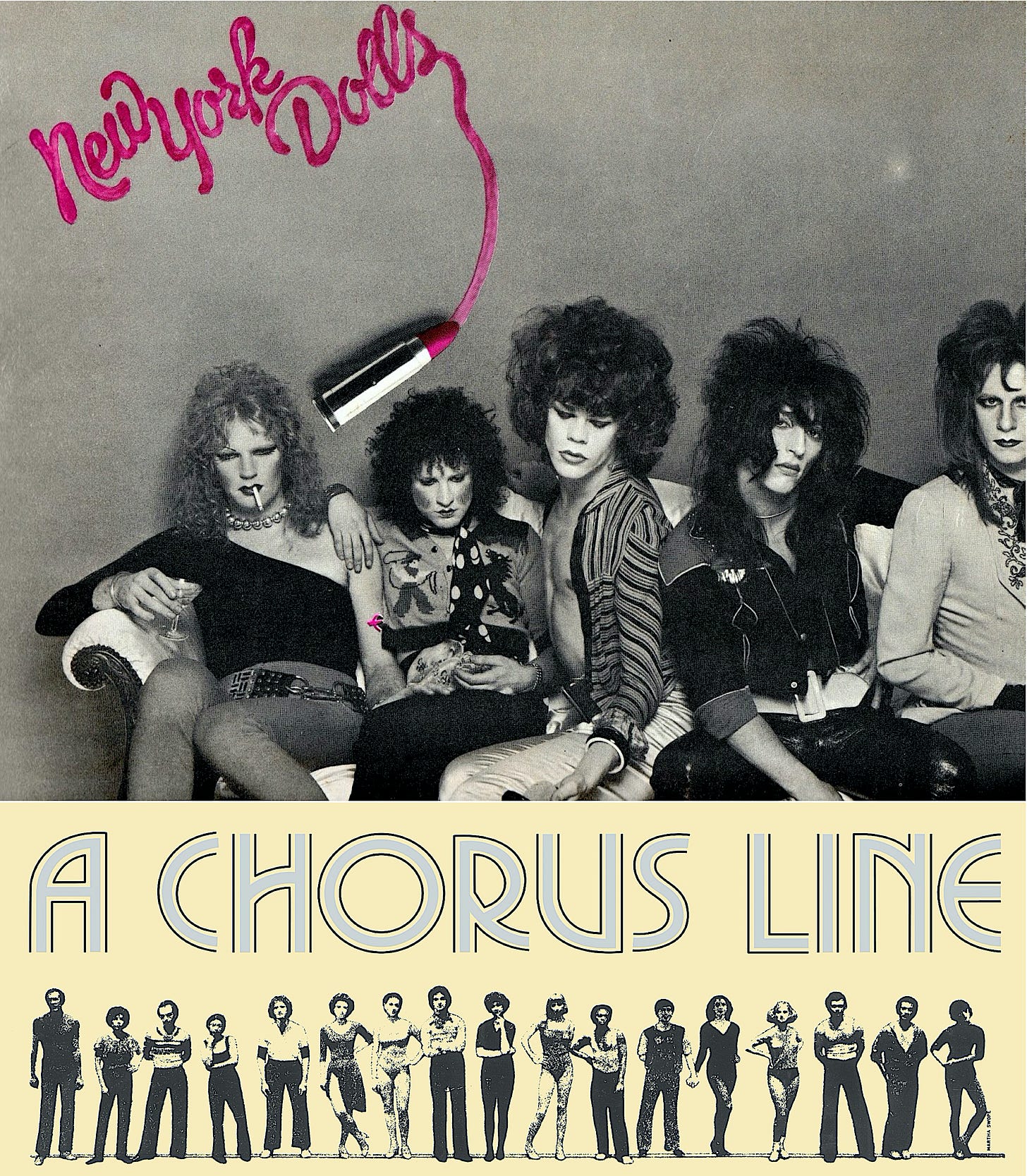

The recent passing of Sylvain Sylvain, rhythm guitarist for the long-departed New York Dolls of blessed memory, has set me to thinking about the Dolls and A Chorus Line. Too much thinking, you might say. Strange but true.

A Chorus Line and the New York Dolls both emerged from the carnage of New York City in the 1970s. Both were conceived as antidotes to the over-commercialized death spiral of their respective artistic domains — rock and roll and the Broadway musical — and both proved perfect remedies ultimately, though not instantly.

I see them as passing ships in the night of New York’s 1970s near-demise. The Dolls’ first known paid gig was in May 1972 at a daft theatrical space called the Mercer Arts Center at 240 Mercer Street, mere blocks from the Public Theater over on Lafayette Street, where A Chorus Line would soon surface. The Mercer Arts Center was a ramshackle culture funhouse carved from part of a once-majestic 19th Century hotel (The Grand Central) - turned-welfare hotel (The University) which, in the first six months of 1972, according to newspapers of the day, witnessed 49 burglaries, 22 robberies, 18 drug-related crimes, seven petty larcenies, six felonious assaults, five grand larcenies, three rapes and one murder.

It was Art D’Lugoff, feckless impresario of the Village Gate, not far away on Bleecker Street, who envisioned the Mercer Arts Center as an Off-Broadway Lincoln Center (literally), with at least six different performance spaces piled into a slice of the eight-story edifice. He and a few partners (who, in fact, soon bought him out) opened the joint in January 1970 with a play called Love and Maple Syrup in the Mercer’s “Hansberry Theatre.” Over the ensuing three years, the Mercer’s longest running theatrical tenants would be The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, by Paul Zindel, and the pre-cinematic adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The Mercer Arts Center’s self-defining gig, however, proved to be the on-again-off-again Tuesday night residency of the New York Dolls in the Mercer’s “Oscar Wilde Room” and, later, its “Sean O’Casey Theatre.”

To help defer the costs of endless repairs and often middling theatrical productions, the Mercer had opened its “Blue Room” cabaret to rock bands from the neighborhood around 1972. Few possessed followings or even much more than fly-by-night existences, but spearheaded by the Dolls, a handful proved antecedent to something that would eventually be called “Punk” after the bands made their way around the corner to a biker bar on the Bowery re-dubbed: CBGB-OMFUG.

The Dolls never made it to CBGB. There isn’t room here to run down all of the train wreck detours in their relatively brief but raucously lived history. The band came together spasmodically as a shifting cast of grungy young rockers from the boroughs before settling into Arthur Kane on bass, Jerry Nolan on drums, John Anthony Genzale, Jr. – aka Johnny Thunders – on lead guitar, David Johansen at the microphone and Sylvain (Ronald) Sylvain (Mizrahi), a Cairo-born Egyptian-Jewish immigrant, on rhythm guitar. Their name seems to have been drawn from the New York Doll Hospital that sat across Lexington Avenue from the clothing store where Sylvain worked for a while. Their sound yoked the dark raunch of the Rolling Stones to a hedonism even more garishly and deliriously out of control, turning the volume up to “11” and sublimely cloaking it all in a cross-dressing kaleidoscope of spangled platform wedgies, teased, bouffant ‘dos, spandex, lamé, lacquered eye-shadow and over-sloshed lipstick. This glam androgyny somehow only made them look more manly, for better or worse. It was pure theater.

The Dolls at the Mercer Arts Center probably reached more people by rumor than physically attended their shows, but all those loud nights did finally manage to get them a record contract with Mercury Records, inked by the visionary rock and roll journalist/A&R man Paul Nelson, whose Minnesota lineage linked him to a very young wannabe folk singer named Bobby Zimmerman, who’d famously stolen a stack of Nelson’s precious folk record collection before heading for New York and changing his name to Bob Dylan. (I got to know Paul during my kid apprenticeship at Rolling Stone Magazine; his office was directly across from the one I shared. I simply loved to listen to the guy talk.)

The Dolls made two smashing albums with Paul Nelson, their only two albums, before finally imploding in 1976. This career implosion was preceded by the actual implosion of the Mercer Arts Center in a cloud of dust on August 3, 1973, brought down by the collapse of the whole goddamn University Hotel from neglect and the destabilizing effect of too many illegal alterations. The Dolls picked up and essentially relocated their residency to the Upstairs playroom at Max’s Kansas City on Park Avenue South and 17th Street. I like to think of them preening there in and around the night of January 26, 1974, when a group of Broadway chorus dancers descended at midnight upon the Nickolaus Exercise Center, just a few blocks north of Max’s on East 23rd Street and Third Avenue, to spiel into a tape recorder about their lives as “gypsies” for the benefit of choreographer Michael Bennett. From those tapes, A Chorus Line was born.

To see the Dolls and A Chorus Line as I’m seeing them you have to envision how down and out the city was in the 1970s – and how that desolation spawned artistic ferment. Great things often happen in the arts after we hit bottom. For many lovers of rock and roll, the ascension of disco in the ‘70s was a kind of farcical apocalypse for the music. The Dolls were the post-apocalyptic retort. On Broadway, similarly, as I wrote in Ever After, “since the latter-1960s, the once reliable musculature for Broadway musical form had continued inexorably to atrophy. What the veteran talents offered now seemed like a withered accretion of gestures.”

A Chorus Line was the revivifying response.

I wonder if any of its gypsies ever saw the Dolls? I wonder if any of the Dolls ever saw A Chorus Line?

Probably not. But you never know.