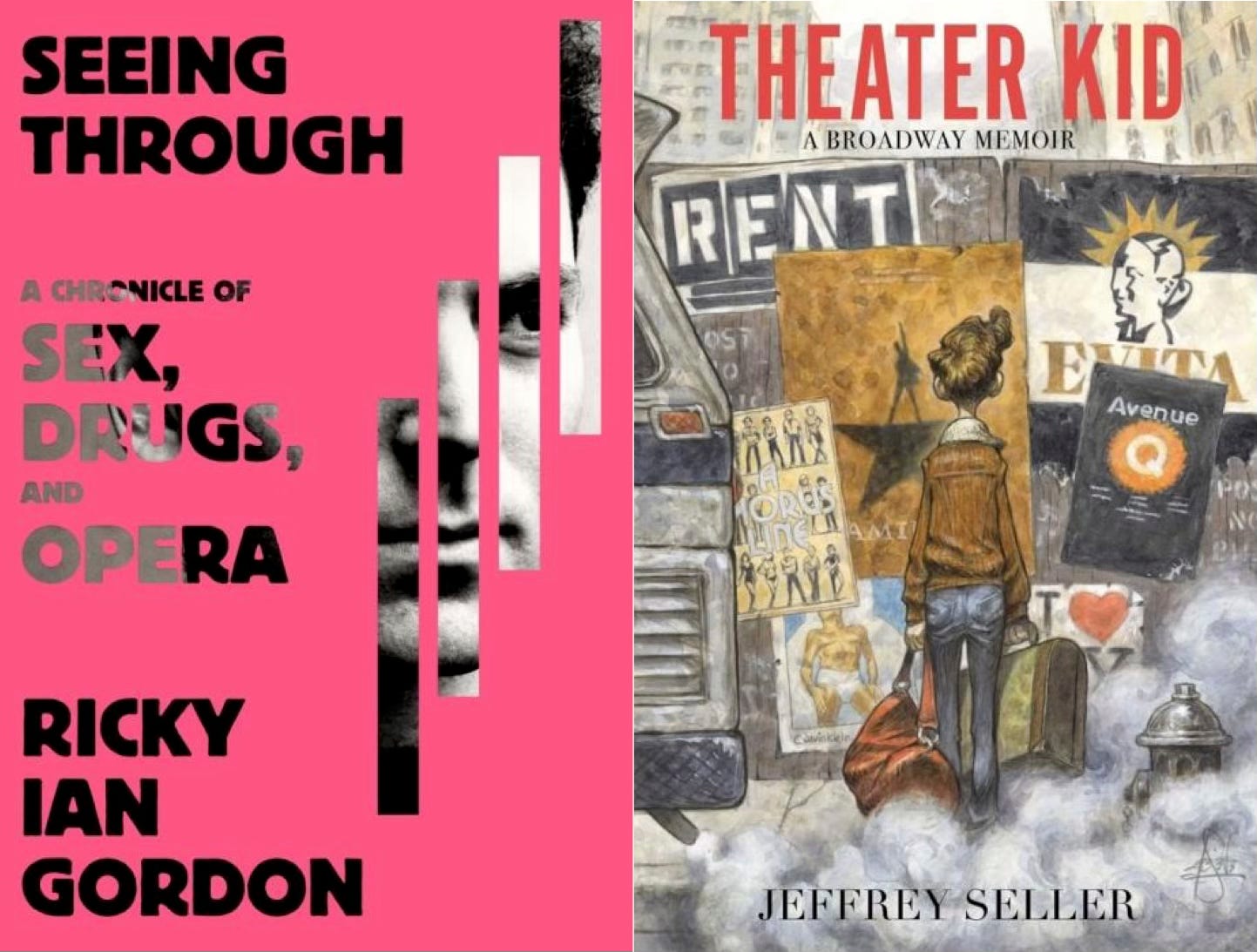

Two Good Books: "SEEING THROUGH" & "THEATER KID"

This is not a book review.

Both of these recently published books that I’m about to share with you were written by friends of mine. Each affected me far beyond friendship. They just might affect you too.

SEEING THROUGH: A Chronicle of Sex, Drugs and Opera is exactly that — a memoir of addictive candor by Ricky Ian Gordon, the prolific and widely esteemed music theater composer, whom I’ve now known, and written about, since he was just setting course toward esteemed. (We first met, I’m pretty sure, at the home of Mary Rodgers, who was Ricky’s early patroness in New York. I first heard Ricky play his own music at Mary’s son, Adam Guettel’s, loft.) How Ricky got from there (in fact, way before there) to here makes for quite a book.

THEATER KID: A Broadway Memoir reconstitutes the singular, at times simply bizarre, childhood and subsequent transformation of Jeffrey Seller into the most successful and influential musical theater producer on Broadway today, beginning with Rent, on through Hamilton. Jeffrey and I met in Jonathan Larson’s living room over one of Jonathan’s “Peasant Feasts," when the utterly unknown Jeffrey insisted that he (and his equally unknown business partner Kevin McCollum) would one day produce the thoroughly unknown Jonathan’s absolutely unknown rock opera. I don’t think I ever completely comprehended what Jeffrey was saying to me that night until I finally read THEATER KID.

The behind-the-scenes backstage quotient in both of these books is consequential; Jeffrey digs into the inside origins of all his hits, as well as his relatively few misses. Ricky does the same for all of his vast and various contemporary operas and musicals. (His exquisite opera of The Grapes of Wrath and his transcendent Intimate Apparel opera are my personal favorites, along with a delicious 2001 Nonesuch album of Ricky’s songs, Bright Eyed Joy.)

The paths to creation for these extraordinary works becomes kind of breathtaking. Yet, that isn’t what these two books are ultimately about.

Most “show business” memoirs dispatch childhood as disposable prelude to the dish of grown-up achievements. For Ricky and Jeffrey, childhood is the abiding story; abusive childhoods, perhaps unsurprisingly, driven by fathers who were destructive in different ways: Ricky’s — physically and verbally, with hyper-macho rage; Jeffrey’s — debilitatingly, torturing his poor family with wildly unstable behavior after a horrific motorcycle accident leaves Dad permanently brain addled. It is only Jeffrey’s diminished dad, however, who manages to express anything approaching unconditional love for his son.

Both of these books are coming-of-age stories, obviously, but more precisely, both are queer coming-of-age stories unfurled with fierce emotional transparency. I have rarely read one, let alone two, more poignant (and, yes, at times rollicking) accounts of youthful sexual discovery; the raucous, raunchy, excruciatingly tentative exploration of what one actually wants from sex, and why.

Inescapably, AIDS is at the heart of both books, particularly for Ricky, who lost a love of his life to the plague. Ricky and Jeffrey lived in an era of existential terror shared with their peers, for years, a terror they make palpable on the page.

Each book also vividly demonstrates how making art can save us. Music saved Ricky. Theater saved Jeffrey. In this grim moment of ignorance, and intolerant assault on the arts, it is essential that we are reminded — as these books so eloquently do — that art is no mere ornament to life, but rather its salvation, the thing we do to comprehend and then share why life is worth living.

Both books are, ultimately, celebrations. Ricky and Jeffrey are great company — erudite, profane, hilarious (a rare combination). Both prove to be damn good writers too, in what, for each, is their first book.

I leave you with this taste: Jeffrey and Ricky, respectively, on the subject of “Home.”

“Cardboard Village. That’s what the kids at school call my neighborhood. I hate the name, coined by a child poet to describe the tar shingles that cover our small house, built fast and cheap on concrete slabs with no basements to protect us from tornadoes in Oak Park, Michigan, the poor enclave in a rising Jewish suburb just north of Detroit.”

— "THEATER KID," Jeffrey Seller

“Our house was a panoply of feminine energy with breasts and vaginas abounding. My sisters were strong personalities, well defined, mercurial. And so was my mother, Eve, the former borscht belt singer and comedian, for whom we were now the audience.”

— "SEEING THROUGH," Ricky Ian Gordon