SS & ME (Part 3 ~ Finis)

The nicest thing that Steve Sondheim ever did for me was entirely unintentional, I think, but I still may be wrong about that. In the Spring of 1992, I asked him for a ticket to Sondheim: A Celebration at Carnegie Hall, which was coming up on June 10 and looked like it was going to be a very big deal. Steve provided one precious ticket — that I paid for with a check made out to his office.

That’s not the thing.

Steve also gave one more ticket to the concert, gratis, to an impoverished and, to me, unknown musical theater composer named Jonathan Larson. Which is how Jonathan came to flop down in the seat beside me that night at Carnegie Hall and — because Jonathan was a very gregarious guy, we wound up talking — mostly about him and the “rock opera” he couldn't stop talking about that he was then writing called Rent.

Since I'd paid for my ticket, I was also on the list for the posh after-party in an upstairs Carnegie Hall aerie. I snuck Jonathan in with me. Together we congratulated Steve on the swell show, thanked him again for the tix and for introducing us… kind of. (Without intent, as I say, but still just the damndest thing, in retrospect). Not that it mattered at the time, to Steve or anybody else. Jonathan soon invited me down to his irresistibly grotty loft in what is now Tribeca (but was then just grotty), where he proceeded to play for me every note of Rent that he'd written so far. And we became friends, good friends. I then watched Rent consume Jonathan for the next three-plus years until he so shockingly and so sadly died on January 25, 1996 — an aortic aneurism the night before his long-obsessed-over rock opera's first preview performance.

I got the news that morning. I was just bereft. And I turned to Steve. Which wasn't easy, since he wasn't speaking to me at the time.

To explain requires a diagram, practically. Over a year before, I'd published two articles in the Spring 1994 issue of Lincoln Center's quarterly magazine, then-called The New Theater Review (now called Lincoln Center Theater Review). Both pieces related to two musicals LCT was producing: a new one called Hello Again, by Michael John LaChiusa, and what would prove to be a historic revival of Carousel. The first essay was titled: “A Shadowy Kinship: Ferenc Molnar and Arthur Schnitzler,” about the pair of Mittel-European playwrights whose plays, respectively Liliom and La Ronde, were the adapted sources for Carousel and Hello Again. The second was “Hooray for What? Collaboration and the Musical Theater,” which is how I got into so much trouble.

My precis (it seemed like a good idea at the time) was that collaboration in musical theater tends to "overrun" titles like Director, Composer, Lyricist. A director's choice can affect a song, a composer's choice can affect the choreography, “allowing for those transcendent moments when titles blur, duties cross and unexpected magic ensues.” One of my examples was the opening number in Company, where the lyric: “We love you…” was sung with the word “love” held by the entire cast for the 15 seconds it took them to descend the working elevator in designer Boris Aronson's set; a decisive moment in the song.

I ascribed the idea for this to the show's director, Hal Prince, who had taken credit for it in an interview I'd read. In fact, I quoted him.

I really should have checked first with Steve. I still can't believe that I didn't.

His call came fairly late one night and was pretty lacerating. “The held note was my idea for the elevator,” he announced. “From the beginning! Hal had nothing to do with it.”

I was mortified. Getting it right was something we often talked about, our shared desire to make sure anything that we wrote had been perfected from every angle; me as a lowly journalist, he as, well...Stephen Sondheim.

“I'll print a correction,” I replied instantly.

“Nobody reads corrections,” he retorted and hung up.

I did ultimately get LCT to run a correction in the next edition of the Review. They thought I was crazy. “We haven't received any complaints,” they insisted. I told them that I had.

Steve and I did not speak for the next year. Still, I reached out to him that awful day in an email because I just could not handle the news about Jonathan. He phoned back almost immediately and was calm and consoling. Jonathan, he basically said, had left the world the musical he had lived to write. His loss was an enormous tragedy. But the musical would now never die.

Our friendship was repaired in this vortex but I don't believe we ever again attended the theater together. He had fallen in love, embarking over the previous year or two on a long-term relationship that he’d waxed on to me about while describing the new musical he was then writing, about love, which would prove to be Passion. Our friendship had never been romantic; he was gay and I was straight, for one thing, plus Steve, in the years I’d known him, had always seemed to be the consummate loner. Still, I had kept him company. Now there was someone to actually sit in his chair, ruin his sleep, and make him aware...

In 1997, I began writing for the New York Times about music and theater. Anything that related to Sondheim, I ran by Steve — solely for the purpose of fact-checking. Not once did he ask for a rewrite of anything that resembled my opinion, but he did straighten out a few points of fact and also copy-edited my prose brilliantly — especially what he considered to be my “abuse of commas.” When I complimented him on his line-editing skills, he revealed to me that if he hadn't become a composer, his dream would have been to sit in a tall chair, wearing a visor, and edit, as in olden days.

With this in mind, when I wrote my book, EVER AFTER: The Last Years of Musical Theater and Beyond, in 2003, about the previous 25 years of musicals on and off Broadway, I not only interviewed him at length (he was marvelously forthcoming), I actually sent him the manuscript, which he proceeded to edit in such detail that I gifted him a bottle of Scotch in gratitude. The book was hugely improved by his gimlet eye.

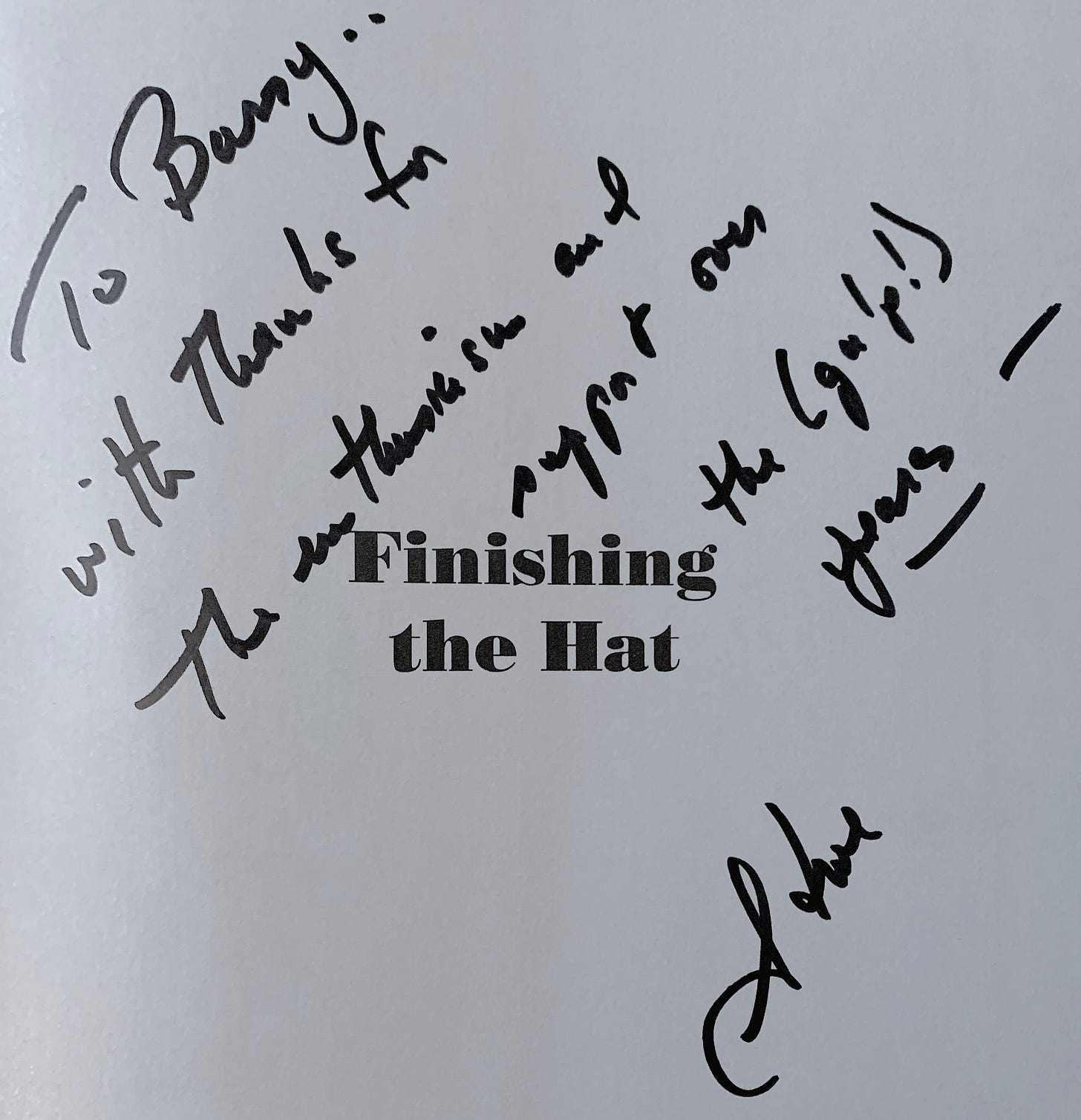

In March 2010, Steve informed me that the book he'd been laboring over, FINISHING THE HAT: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981), would finally be coming out in the Fall. I offered to throw him a publishing party at my bookstore, Chartwell Booksellers. He accepted. The night was, of course, an absolute blast; Monday, October 25, 2010. The invitation list was all Steve's, and attendees ranged from Mike Nichols, Stanley Donen, William Goldman, to Barbara Cook (whose birthday was October 25; Steve led the crowd in singing “Happy Birthday”). I got the thrill of introducing my daughters, 7-year-old Lea and 5-year-old Sara, to Steve. I also brought in a piano and a terrific quartet of performers — Judy Kuhn, Malcolm Getz and David Pittu, accompanied by Lawrence Yurman — to sing a few songs; despite Steve's insistence that nobody came to a book party to hear music, they came to drink. Just before the show began, I looked up from our table, in a room packed with Steve's pals, to see him seated alone at his table. I guess even his pals were too awed to join him. I grabbed my family and we did.

A little over a year later, on December 2, 2011, I threw another party for his second volume, LOOK, I MADE A HAT: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011). This time we dispensed with any performances, as he’d adamantly advocated; just a piano player tinkling Sondheim songs in the background and the same crowd, basically, just drinking. Steve and Bill Goldman were the last to leave.

Over the past decade our contact was almost exclusively by email, interspersed with a handful of after-work cocktails at his home. More and more of his time was spent at his Connecticut house in the country. In 2017 he got married, and contentment — a word I never before would have thought to use, but always wished for Steve — suddenly seemed to apply.

The alacrity with which he responded to my querying emails nevertheless astonished me. One quickie, about a Playbill article I was working on for a one-night-only benefit performance at Second Stage Theater in March 2019 of Saturday Night — his first Broadway-bound (but ultimately not then-produced) 1955 musical — brought an instantaneous reply that included something of a scoop: The fact that Bob Fosse, as potential director/choreographer, had worked a day of auditions for a 1959 renewal of the project, to be produced by Jule Styne, before Steve pulled the plug on the whole thing because, as he put it: “I didn't want to revisit old work.”

We emailed regularly throughout the pandemic. I kept checking in to make sure he was okay, which he was. I sent him the manuscript for a new, expanded edition of EVER AFTER that took the book right up to the day the lights were turned out on Broadway in March 2020. He reminded me that he was a very slow reader, “so be patient,” and asked for a full print out, rather than the PDF I'd sent. I obliged. Then came one of the last things he ever said to me, an email that began: “Thanks so much, Barry.

Because I couldn’t wait, I made the mistake of reading the Introduction and browsing through the first chapter. I fought the urge to continue when I saw you refer to “Stephen Sondheim and Harold Prince’s ... Sweeney Todd.” What happened to Hugh Wheeler? Since when is a director called a creator? Hal did a wonderful job of directing it, but he had nothing to do with the creation — that was the sole province of Chris Bond, Hugh and me.

In any event, I’ll wait until I get over my irritation before I settle down to read it, which I look forward to doing. Meanwhile, good luck with it.

Steve